Citizenship of the European Union

| European Union |

This article is part of the series: |

|

Policies and issues

|

|

Foreign relations

|

Citizenship of the European Union was introduced by the Maastricht Treaty signed in 1992, and in force as of 1993. It exists alongside national citizenship and provides additional rights to nationals of Member States of the European Union.

Contents |

Who is an EU citizen?

Article 20 (1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union[1] states that

Citizenship of the Union is hereby established. Every person holding the nationality of a Member State shall be a citizen of the Union. Citizenship of the Union shall be additional to and not replace national citizenship.

All nationals of Member States are citizens of the union. "It is for each Member State, having due regard to Community law, to lay down the conditions for the acquisition and loss of nationality." [2]

Rights of EU citizens

Specific rights

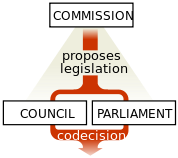

The Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union[1] provides the following rights to EU citizens:

- a right to access to European Parliament, Council, and Commission documents (Article 15).

- a right not to be discriminated against on grounds of nationality within the scope of application of the Treaty (Article 18);

- the right of free movement and residence throughout the Union and the right to apply to work in any position (including national civil services with the exception of those posts in the public sector that involve the exercise of powers conferred by public law and the safeguard of general interests of the State or local authorities (Article 21) for which however there is no one single definition;

- the right to vote and the right to stand in local and European elections in any Member State, other than the citizen's own, under the same conditions as the nationals of that state (Article 22);

- the right to petition the European Parliament and the right to apply to the European Ombudsman in order to bring to his attention any cases of poor administration by the EU institutions and bodies, with the exception of the legal bodies (Article 24)[3]; and

- the right to protection by the diplomatic or consular authorities of other Member States when in a non-EU Member State, if there are no diplomatic or consular authorities from the citizen's own state (Article 23);[4]

- the right to apply to the EU institutions in one of the official languages and to receive a reply in that same language (Article 24).

The right to residence for nationals of the two most recent EU members (Romania and Bulgaria) may be limited by member states. However, such limitations can only be imposed in the seven years following those countries' accession, i.e. until the end of 2013. At the year 2013 the restrictions by these two EU Member States shall be lifted permanently.

Article 21 Freedom to move and reside

Article 21 (1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union[1] states that

Every citizen of the Union shall have the right to move and reside freely within the territory of the Member States, subject to the limitations and conditions laid down in this Treaty and by the measures adopted to give it effect.

The European Court of Justice has remarked that,

EU Citizenship is destined to be the fundamental status of nationals of the Member States[5]

The ECJ has held that this Article confers a directly effective right upon citizens to reside in another Member State.[5][6] Before the case of Baumbast,[6] it was widely assumed that non-economically active citizens had no rights to residence deriving directly from the EU Treaty, only from directives created under the Treaty. In Baumbast, however, the ECJ held that (the then[7]) Article 18 of the EC Treaty granted a generally applicable right to residency, which is limited by secondary legislation, but only where that secondary legislation is proportionate.[8] Member States can distinguish between nationals and Union citizens but only if the provisions satisfy the test of proportionality.[9] Migrant EU citizens have a "legitimate expectation of a limited degree of financial solidarity... having regard to their degree of integration into the host society"[10] Length of time is a particularly important factor when considering the degree of integration.

The ECJ's case law on citizenship has been criticised for subjecting an increasing number of national rules to the proportionality assessment.[9]

Article 45 Freedom of movement to work

Article 45 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union[1] states that

1. Freedom of movement for workers shall be secured within the Union.

2. Such freedom of movement shall entail the abolition of any discrimination based on nationality between workers of the Member States as regards employment, remuneration and other conditions of work and employment.

However state employment reserved exclusively for nationals varies immensely between member states( e.g. training as a barrister in Britain and Ireland is not reserved for nationals; the corresponding French course qualifies one as a 'juge' and hence can only be taken by French citizens).

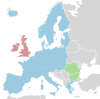

It is not unusual, however, for new member states to have to undergo transitional regimes during which their nationals only enjoy restricted access to the labour markets in other member states. This most recently occurred on the 2004 and 2007 enlargements. In the 2004 enlargement three "old" member states—Ireland, Sweden and the United Kingdom—decided to allow unrestricted access to their labour markets. And as of December 2009, all but two member states—Austria and Germany—have completely dropped controls. These restrictions will expire on 1 May 2011.[11]

All pre-2004 member states, bar Finland and Sweden, imposed restrictions on Bulgarian and Romanian citizens following the 2007 enlargement, as did two member states that joined in 2004: Malta and Hungary. These restrictions will expire on 1 January 2014.[11]

Citizens Rights Directive

Much of the existing secondary legislation and case law was consolidated[12] in Directive 2004/38/EC on the right to move and reside freely within the EU.[13]

History

The concept of EU citizenship as a distinct concept was first introduced by the Maastricht Treaty, and was extended by the Treaty of Amsterdam.[14] Prior to the 1992 Maastricht Treaty, the European Communities treaties provided guarantees for the free movement of economically active persons, but not, generally, for others. The 1951 Treaty of Paris[15] establishing the European Coal and Steel Community established a right to free movement for workers in these industries and the 1957 Treaty of Rome[16] provided for the free movement of workers and services.

However, the Treaty provisions were interpreted by the European Court of Justice not as having a narrow economic purpose, but rather a wider social and economic purpose.[17] In Levin,[18] the Court found that the "freedom to take up employment was important, not just as a means towards the creation of a single market for the benefit of the Member State economies, but as a right for the worker to raise her or his standard of living".[17] Under the ECJ caselaw, the rights of free movement of workers applies regardless of the worker's purpose in taking up employment abroad,[18] to both part-time and full-time work,[18] and whether or not the worker required additional financial assistance from the Member State into which he moves.[19] Since, the ECJ has held[20] that a recipient of service has free movement rights under the treaty and this criterion is easily fulfilled,[21] effectively every national of an EU country within another Member State, whether economically active or not, had a right under Article 12 of the European Community Treaty to non-discrimination even prior to the Maastricht Treaty.[22]

In Martinez Sala,[23] the European Court of Justice held that the citizenship provisions provided substantive free movement rights in addition to those already granted by Community law.

See also

- Passport of the European Union

- European Citizens' Initiative

- European citizens' consultations

- Europe for Citizens

- Four Freedoms (European Union)

Further reading

- Maas, Willem (2007). Creating European Citizens. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-5485-6; ISBN 978-0-7425-5486-3 (paperback).

- Meehan, Elizabeth (1993). Citizenship and the European Community. London: Sage. ISBN 978-0-8039-8429-5.

- O'Leary, Síofra (1996). The Evolving Concept of Community Citizenship. The Hague: Kluwer Law International. ISBN 978-9-0411-0878-4.

- Soysal, Yasemin (1994). Limits of Citizenship. Migrants and Postnational Membership in Europe. University of Chicago Press.

- Wiener, Antje (1998). 'European' Citizenship Practice: Building Institutions of a Non-State. Boulder: Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-3689-9.

- European Commission. "Right of Union citizens and their family members to move and reside freely within the territory of the Member States". http://europa.eu/legislation_summaries/education_training_youth/lifelong_learning/l33152_en.htm.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Treaty on the Function of the European Union (consolidated version)

- ↑ Case C-396/90 Micheletti v. Delegación del Gobierno en Cantabria, which established that dual-nationals of a Member State and a non-Member State were entitled to freedom of movement; case C-192/99 R v. Secretary of State for the Home Department, ex p. Manjit Kaur. It is not an abuse of process to acquire nationality in a Member State solely to take advantage of free movement rights in other Member States: case C-200/02 Kunqian Catherine Zhu and Man Lavette Chen v Secretary of State for the Home Department.

- ↑ This right also extends to "any natural or legal person residing or having its registered office in a Member State": Treaty of Rome (consolidated version), Article 194.

- ↑ This is due to member states not having an embassy in all third countries: The following countries host only a single Embassy of EU member state: Antigua and Barbuda (UK), Barbados (UK), Belize (UK), Central African Republic (France), Comoros (France), Djibouti (France), Gambia (UK), Guyana (UK), Lesotho (Ireland), Liberia (Germany), Saint Vincent and the Grenadines (UK), San Marino (Italy), São Tomé and Príncipe (Portugal), Solomon Islands (UK), Timor-Leste (Portugal), Vanuatu (France).

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Case C-184/99 Rudy Grzelczyk v Centre public d'aide sociale d'Ottignies-Louvain-la-Neuve .

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Case C-413/99 Baumbast and R v Secretary of State for the Home Department, para. [85]-[91].

- ↑ Now article 20

- ↑ Durham European Law Institute, European Law Lecture 2005, p. 5.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Anthony Arnull; Alan Dashwood; Michael Dougan; Malcolm Ross; Eleanor Spaventa and Derrick Wyatt.; Wyatt, D., Dashwood, A. and others (2006). European Union Law (5th ed.). Sweet & Maxwell. ISBN 978-0421925601.

- ↑ "The constitutional dimension to the case law on Union citizenship". European Law Review 31 (5): 613–641. 2006.. See also Case C-209/03 R (Dany Bidar) v. London Borough of Ealing and Secretary of State for Education and Skills, para. [56]-[59].

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Free movement of labour in the EU 27". Euractiv. 25 November 2009. http://www.euractiv.com/en/socialeurope/free-movement-labour-eu-27/article-129648#. Retrieved 27 December 2009.

- ↑ European Commission. "Right of Union citizens and their family members to move and reside freely within the territory of the Member States". http://europa.eu/legislation_summaries/education_training_youth/lifelong_learning/l33152_en.htm. Retrieved 2007-12-26.

- ↑ Directive 2004/38/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 on the right of citizens of the Union and their family members to move and reside freely within the territory of the Member States.

- ↑ This rendered the provision to the same effect in Protocol no. 5 on the position of Denmark in the Treaty on the European Union superfluous. See Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Denmark. "The Danish Opt-Outs". http://www.denmark.dk/en/menu/AboutDenmark/GovernmentPolitics/DenmarkAndTheEU/TheDanishOptouts/. Retrieved 2007-11-24.

- ↑ Article 69.

- ↑ Title 3.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Craig, P., de Búrca, G. (2003). EU Law: Text, Cases and Materials (3rd ed.). Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 706–711. ISBN 0-19-925608-X.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Case 53/81 D.M. Levin v Staatssecretaris van Justitie.

- ↑ Case 139/85 R. H. Kempf v Staatssecretaris van Justitie.

- ↑ Joined cases 286/82 and 26/83 Graziana Luisi and Giuseppe Carbone v Ministero del Tesoro.

- ↑ Case 186/87 Ian William Cowan v Trésor public.

- ↑ Advocate General Jacobs' Opinion in Case C-274/96 Criminal proceedings against Horst Otto Bickel and Ulrich Franz at paragraph [19].

- ↑ Case C-85/96 María Martínez Sala v Freistaat Bayern.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||